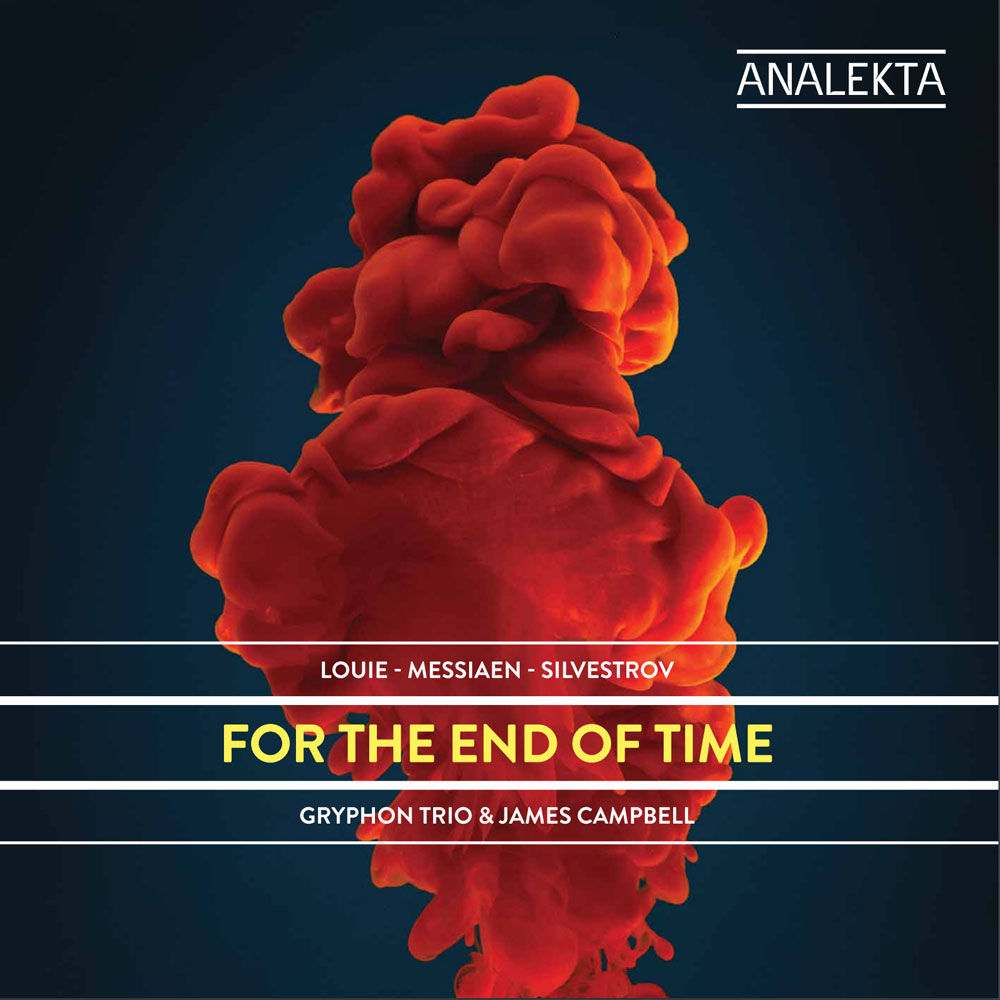

Louie, Messiaen, Silvestrov: For the End of Time

“Stalag VIIIA, Görlitz. Première of the Quatuor pour la fin du temps by Olivier Messiaen. January 15, 1941. Performed by Olivier Messiaen, Etienne Pasquier, Jean Le Boulaire, and Henri Akoka.” Cellist Etienne Pasquier kept these words – printed on a faded Art Nouveau-style invitation to the première of one of the most seminal chamber works of the 20th century – in his breast pocket until his death, in his nineties. The chillingly named Stalag VIIIA was a camp in Silesia, about 70 miles east of Dresden, for prisoners of war of enlisted rank. A series of extraordinary coincidences led to the creation of Messiaen’s powerful masterpiece. Remarkably, Messiaen, a prisoner since the summer of 1940, was not only allowed, but encouraged to compose music. A German officer named Karl-Albert Brüll, gave him a regular supply of manuscript paper, pencils, erasers – and bread. Clarinettist Henri Akoka was Jewish but, in Stalag VIIIA, being a French rather than East European Jew, he was incarcerated under the same terms as his non-Jewish French fellow prisoners. Messiaen had already met Akoka, a clarinettist with the Orchestre National, and Pasquier, a professional cellist, in Verdun, where the French composer had been sent as a medical orderly. Messiaen and Pasquier would listen to the dawn chorus of birds on their morning watch. Messiaen would note down individual bird songs with a precision that would soon blossom into a skill unmatched by any composer. Using these notated birdsongs as inspiration, he began to write a piece for solo clarinet, calling it Abyss of the Birds. Then, the concept grew when the trio met up with violinist Jean Le Boulaire in the Görlitz camp. The work’s instrumentation was now for violin, clarinet, cello and piano and it was ground-breaking. Messiaen was to deal with the challenges of blend and balance throughout by subdividing the quartet and using the full potential of all four instruments sparingly.

Messiaen’s devout religious beliefs underpinned his work on the Quartet. He found hope in the vision of St. John, the angel, wrapped in cloud and crowned with a rainbow [Revelation 10.1–7**]. “I finally wrote this quartet, dedicating it to this angel who declared the end of Time,” Messiaen said in one of many interviews after his liberation. As the details of the story evolved and became the stuff of legend over the years, the constant element remained Messiaen’s faith. “I love Time,” Messiaen wrote, “because it’s the starting point of all creation.” Temporal freedom defines Messiaen’s relationship with the divine and, in a preface to the quartet, he writes: “The special rhythms, independent of the metre, powerfully contribute to the effect of banishing the temporal.” The eight-movement substantial structure of the piece also contributes to its feeling of endlessness and to a lack of traditional sequential development. Its emotional trajectory is enormous, from the opening dawn chorus, with fragments of birdsong on violin and clarinet woven with revolving sequences on piano and cello, to the terrifying Dance of the Fury, with all four instruments pounding out a repeated melody devoid of harmony, for more than six minutes. The Quartet is anchored by two ecstatic paeans of great ethereal beauty, the first for cello, and the second for violin, both with piano accompaniment. Their slow tempo and feeling of finality disorient our expectations of how a piece of chamber music should unfold. “This is the subject of the Quartet,” Messiaen’s second wife, the pianist Yvonne Loriod said after his death. “At the end of Time, when the universe is no more, it will drift into Eternity. And this is the riddle that fascinated my husband.”

Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov also explores the expressive power of Time, often looking to the past to feed a prolific contemporary creativity. His music can reflect on and enter into dialogue with fragments of music by composers as diverse as Schubert, Schumann, Mahler, Wagner, Glinka and Bach. “I do not write new music,” he has said. “My music is a response to and an echo of what already exists.” Silvestrov has long pursued an individual path. In the late 1960s, his music was championed and performed in the West by Maderna and Boulez. But Silvestrov valued his independence from what was then in vogue. “The most important lesson of the avant-garde,” he said of this period, “was to be free of all preconceived ideas – particularly those of the avant-garde.” Even under the ever-watchful eye of communist party officials, Silvestrov continued to seek an individual voice. In 1974, he resigned from the Composers’ Union and, therefore, from any official employment as a composer. He began to evolve what has come to be known as his ‘metaphorical’ style in which echoes of often romantic sounds and poetic allusions are woven into a highly developed feeling for structure. Silvestrov’s ‘meta-music’ echoes Western post-modernism and has been enthusiastically received in recent years.

Fugitive Visions of Mozart… resulted from a 2007 commission from the Gryphon Trio. After sending recordings, including their Analekta recording of the Mozart Piano Trios, the Gryphon Trio worked with the 70 year-old composer and gave the première at the Lviv Contasts Festival, October 3, 2007, followed closely by a performance in Kyiv (Kiev). The piece is Silvestrov’s second piano trio, a successor to, but very different from, his Drama for piano trio of 1970/71. The music falls into six distinctive sections (or visions), played without a break. The mood is nocturnal and dreamlike, with Silvestrov’s themes fleetingly sounding like quotations, without being derivative. The enigmatic second and lilting fourth visions also bring to mind Prokofiev’s Visions fugitives, Op. 22, for piano, whose poetic title is borrowed. Cellist Roman Borys says that Silvestrov’s “delicate colours combine to create contemplative moments of intense beauty resulting in a remarkable work that is unlike anything in the repertoire.”

© Keith Horner

* as recounted in Rebecca Rischin’s 2003 book For the End of Time – The Story of the Messiaen Quartet (Cornell University Press)

** “I saw a mighty angel coming down from heaven, wrapped in cloud, with a rainbow round his head. His face was like the sun, his feet like pillars of fire. He planted his right foot on the sea, his left on the land and, standing on the sea and the earth, he raised his hand to heaven and swore by Him who lives for ever and ever, saying: There shall be no more time; but on the day the seventh angel sounds the trumpet, the hidden purpose of God will have been fulfilled.” [Revelation 10.1–7]