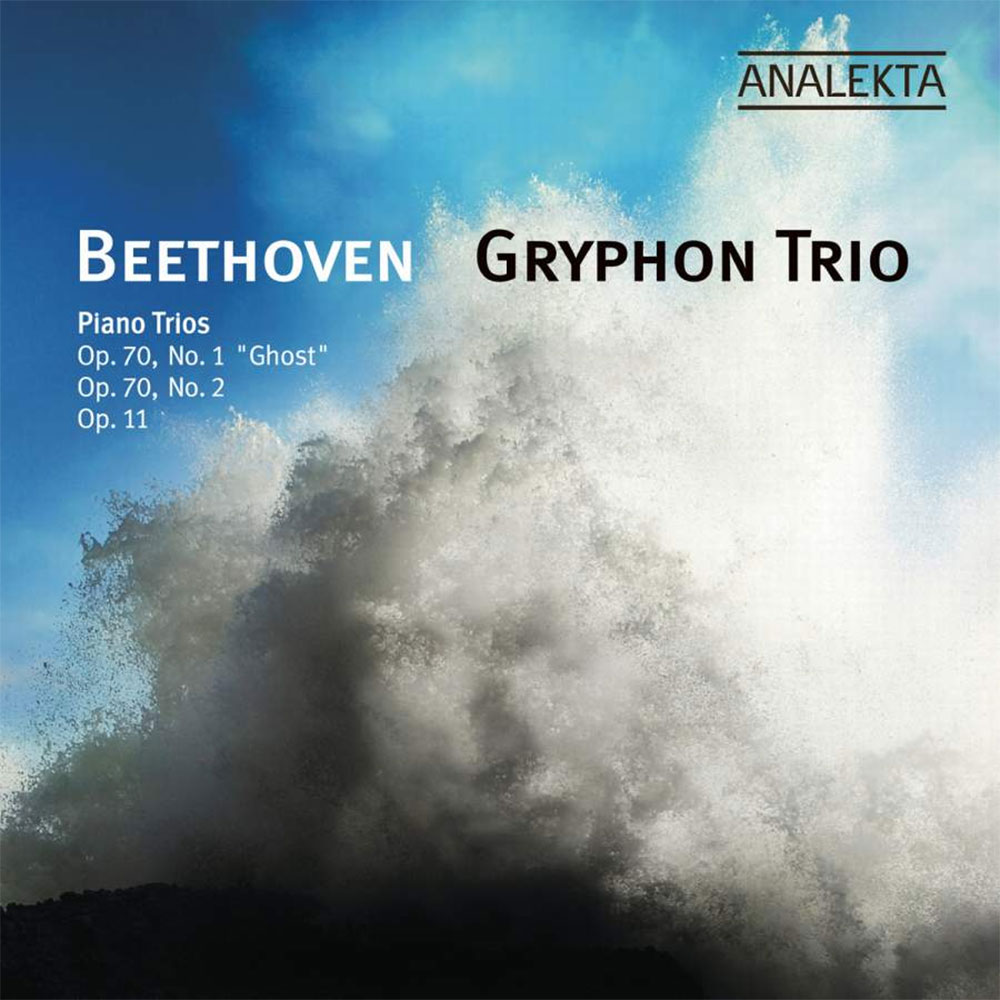

Beethoven: Piano Trios Op. 70 No. 1 “Ghost” & No. 2; Op. 11

These finely judged and warmly recorded performances gave me great deal of pleasure.

Buy this Recording

Let the earth hide thee!

Thy bones are marrowless, thy blood is cold ;

Thou hast no speculation in those eyes

Which thou dost glare with.

So reacts Macbeth to the sight of Banquo’s Ghost, a reminder of his murderous deed. Although Beethoven abandoned a planned opera on Shakespeare’s Macbeth as “too gloomy”, a clue as to what the music might have sounded like survives in the mysterious slow movement of his D major Piano Trio. Indeed, juxtaposed with plans for the aborted opera in his sketchbook of 1808 is a sketch for this Largo whose shimmering piano tremolos and ghoulish atmosphere Beethoven’s star pupil Carl Czerny called “an appearance from the underworld”. Since this pronouncement the trio has been popularly known as the “Ghost”.

The weighty central Largo assai ed espressivo, in D minor, unfolds stealthily. A three note sotto voce unison motif in the strings and an ornamented turn in the piano sustain the entire movement. Extraordinary piano tremolos, now in the bass, now in the treble, now fortissimo, now pianissimo, accompany the relentless forward march of these initial motifs. A fleeting episode in D major offers a glimmer of light. But it is short-lived, and soon the music reaches a terrifying climax. A chromatic scale in the piano that plunges nearly five octaves recalls the unrepenting Don Giovanni’s descent into the flames of Hell at the conclusion of Mozart’s opera.

This spectral movement is flanked by two earthly appendages in D major. The first, an Allegro vivace e con brio, opens with a fiery unison motto followed immediately by a dolce theme. The desolate pianississimo unisons that end the exposition seem to foreshadow the mood of the Largo. A contrapuntally involved development requires two attempts to launch the recapitulation: only in the second does the movement’s motto sound in the tonic. On the other side of the abyss is a Presto finale that some consider too lighthearted after the horror that is the Largo. But what of the comical drunken Porter’s scene that immediately follows Macbeth’s grizzly midnight murder of King Duncan? In this way, the finale’s quirky chromatic scales and its off-kilter folksiness seem to offer just the right measure of dramatic relief.

Beethoven completed the “Ghost” (and its companion, Op. 70, No. 2) in 1808 while summering in a village just outside Vienna, immediately after finishing the Sixth Symphony (“Pastoral”). While the “Ghost” impresses with its intense dramatic flair, Op. 70, No. 2 explores another world entirely, that of subtle emotions and classical restraint. As Donald F. Tovey remarked, here Beethoven achieves an unparalleled “integration of Mozart’s and Haydn’s resources, with results that transcend all possibility of resemblance to the style of their origins”. Haydn’s influence is already apparent in the first movement, marked Poco sos tenuto — Allegro ma non troppo. It opens with a slow introduction whose mournful melody and stark lines return several times, including at the very end, taking after Haydn’s “Drumroll” symphony. These passages interrupt the music’s otherwise carefree demeanor like cloudy, though fleeting, thoughts or reminiscences.

The Allegretto begins with a charming theme punctuated by an amusing reverse dotted figure (short-long). One imagines a nobleman elegantly flicking crumbs off a table. But in the second theme, in the parallel minor, the mood becomes portentous, even Baroque in its rhythmic pounding. And so the movement unfolds, alternating between cheery flicking and ominous pounding, before finally dissipating entirely. Cast in double-variation form, a favourite of Haydn’s, it again shows Beethoven’s indebtedness to his former teacher.

But in the relaxed, waltz-like Allegretto ma non troppo that follows, Beethoven conjures up non-Classical realms. Antiphonal exchanges between strings and piano (double-stopping in the violin make the two stringed instruments sound like three) possess a Renaissance flavour while mysterious harmonic twists anticipate Schubert.

Then in the robust Allegro finale, in place of Haydn’s guiding hand, come the bold gestures, jarring surprises and general boisterousness that only Beethoven could have written. From innovative third-related key relations to the widening of the upper compass of the piano, this is Beethoven searching for new paths and effects. Perhaps most remarkable — and Beethovenian — is the structure: the recapitulation contains as much development of the principal themes as the development section itself.

Thirteen years separate Beethoven’s Op. 70 from his initial forays in the genre, the three Op. 1 trios of 1795. In the interval, Beethoven’s only work for piano trio, Op. 11 of 1798, actually began its life as a trio for clarinet, cello and piano. In order to boost sales, however, this light and cheerful work — whose three movements all end with a bit of surprise — was published for either clarinet or violin, the two parts being nearly identical.

The opening Allegro con brio bounds along, propelled by an active piano part that interacts playfully with the strings. A singing cello in its tenor register introduces the lyrical Adagio. When the tune passes to the violin, its companions supply interjections and imitations. The proceedings reach a magically hushed pianissimo in which short cello fragments are answered by gently flowing rivulets in the piano.

The finale, marked Allegretto, is a theme and variations on an immensely popular tune, “Pria ch’io l’impegno”, from the 1797 comic opera L’amor marinaro (Love at Sea) by Joseph Weigl (1766-1846), a once famous and now forgotten composer. In the opera, Captain Libeccio, his servant Pasquale and Cisolfautt, a partially deaf music master rescued at sea by the Captain, sing a terzetto in which Cisolfautt (whose name consists of solfege syllables) declares: “Before I take on this magisterial task, I must have a snack.” He then warns that, “You will know what I am all about if my stomach raises a high note by a sharp.” Beethoven’s nine variations, dramatic in conception, cover a wide range of expression. And he surely intended that you laugh — or at least smile — at the downright comical ending in which, if you listen carefully, you will hear poor Cisolfautt’s stomach rumbling.

© Robert Rival